That night was cold.

While the sleeping bags are rated for temperatures down to -60°C, this basically means that you will survive at those temperatures - it doesn't mean comfortably so. And while -35°C is still quite a bit warmer than that, the sleeping bag doesn't really get nice and warm inside, just a lot less cold than not being in it.

I did get some sleep that night, but not a lot of it. Constanze and Chuck fared worse. While sleeping outside under the stars was an interesting experience, it was also a fairly uncomfortable one. It later turned out that her sleeping bag was put together in the wrong way. The sleeping bag has a fairly clever system that zips an inner sleeping bag to an outer one, so that you still only need to open one zipper to get in and out of the whole thing. Trouble was that the zippers were attached the wrong way, which, instead of creating a well-designed structure of one sleeping bag within another, basically created just one large rolled blanket. No wonder the sleeping bag wasn't working as well as it was supposed to. Chuck also didn't sleep much (or at all) that night and mentioned in the morning that his toes felt like blocks of ice.

The original plan was to sled for about 45 kilometers that day, camp, and then do the same distance to get to Shingle Point the following day (where we would be in a cabin).

Frank got a bit concerned that three of us mentioned being cold (because with environment like this we shouldn't have been) and he was specifically worried about me being cold. (Primarily because I usually am not. So far I had been dog sledding with a medium strength fleece shirt and a leather jacket and hadn't minded. I had a thick parka with me, but so far it had just been carried on my sled. So me feeling cold seemed somewhat worrying, even though I didn't worry about it myself. It was just a cold night and I hadn't slept well.) At that point, we didn't know that Constanze had been cold due to the wrong configuration of her sleeping bag and Chuck had been freezing, well, because he had been freezing.

But it seemed like a good idea to change the original plan. There was nothing special about going 45 kilometers, as there was no specific camping place between Shallow Bay and the cabin at Shingle Point, so we might as well go 30 or 60 kilometers or any other distance and camp there.

Or we might just try to get to the cabin in a single day. For us clients, it seemed like an option - get going and see how far we get. If we get all the way - fine. But if we go 70 kilometers, we could also just camp there and have a leisurely run the following day. Although it seems in retrospect that Frank was pretty committed to get us to the cabin and not stop on the way.

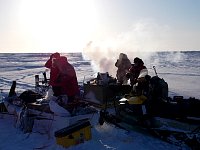

So after some hearty (though probably not healthy) breakfast, we were on our way.

We were in for a long run.

While I'm generally fond of dogsledding and can't get enough of it, my excitement admittedly waned a bit after standing on the sled for more than 10 hours.

And that were fairly continuous 10 hours of sledding. The longest break was a lunch break of ten minute length, where we also gave the dogs some snacks and Frank came down the line and distributed a cold sausage to each of us. And then we were off again. (But, given the breakfast we had, we could probably have gone on for two days before anyone of us would have gotten hungry. The point is not that we lacked food, but that we did go on in a pretty determined fashion and did more 'dog driving' than 'tourist mushing'.)

Going on more than ten hours of a dog sled is not that bad by itself - after a while I decided that it would be a good idea to wear the warm parka instead of the leather jacket, but otherwise it was mostly a comfortable ride. It only got tedious and tricky towards the end, since the sun had already gone down and it was hard to see the shape of the trail ahead in the diffuse light. So it got harder to anticipate the movement of the sled due to bumps and snowdrifts and not falling off the sled was more of an effort.

Especially since the trail got trickier now. So far, we had been going on snow covered sea ice. Which had some slow passages where the dogs had to go through soft snow (and we needed to help the dogs by pushing the sleds), but it was fairly straightforward and flat. But now we crossed a bit of a land, so the trail had more bumps and up-and-down passages to them and there were also a couple of bits with sheer ice to cross. All fun stuff to do, but hard to see in the twilight and at that point (about nine hours down the trail), we were also getting a bit tired.

Probably the dogs were getting tired as well. While they can run for longer distances if needed, none of the dogs had been in races or on longer tours. All they knew was the normal tours they did back home in Whitehorse, where the camping spots are about 30 kilometers apart. So they were probably a bit perplexed when we didn't stop after their 'usual daily distance', but just expected them to continue for about three times that distance.

After ten-and-a-half hours and almost 90 kilometers we reached the hut at Shingle Point.

All of us were probably a bit exhausted - but then, we didn't need to put up the tents. And we would be sleeping warm tonight.

And the place had an outhouse, which is always an appreciated feature.

It was even a 'deluxe designer toilet', according to its inscription.

Though it should be noted that the hut is primarily intended for summer use. And while surely durable, a metal toilet seat has some disadvantages at -30°C (this night wasn't quite as cold as the previous one). Still, a lot better than squatting on the snow.

The hut wasn't as large as Edward's cabin had been, but it was still more spacious than the tents. So after taking care of the dogs, we had a nice, late dinner (it was around midnight by then) and went to bed.

And then tried to get some cooler place to sleep.

The stove heated the place quite well, but there was a significant temperature drop from the top bunk to the floor. And even though Peter is from northern Australia (which is known for being fairly warm all year round), even he found the top bunk too warm for sleeping. And while I was staying at lower bunk level, I still went outside in the middle of the night, just to stand there for five minutes and cool down a bit before getting back to my sleeping bag. (Quite the opposite situation to the previous night.) And then moved my sleeping bag down to the floor in the morning.

But everyone could be as warm as they pleased. It was a good decision to go for the hut.

How good the decision was only became apparent the next morning.

Chuck changed his socks and got a look at his toes. And three of them had the purple-black colour of ripe blueberries. Which is not a good colour for toes to have.

So when his toes felt like blocks of ice the previous night, this wasn't just metaphorically so.

So we had a small crisis on our hands. Which is why nobody looks overly happy in the following pictures.

While Chuck wasn't in any pain (he hadn't really noticed the problem until he got a look at his toes) or immediate danger, it was clear that we couldn't just continue. He needed to get medical help. And soon.

So we used the sat phone (which, luckily, we had with us) to call emergency services.

Note 1: Surprisingly, a sat phone wasn't 'standard equipment' for the trip and Frank only carried it because someone (I think his daughter) gave it to him 'just in case'. Usually he's happy just to have a SPOT (which is a kind of satellite supported emergency beacon) with him. And while a SPOT is great in life-or-death situations where a full search-and-recue is required, it is quite limited if a more specific assistance is needed. A SPOT (essentially) has two buttons. On for requesting a full search-and-rescue operation and one to send a pre-programmed e-mail (which is sent from a SPOT server and can't be changed from the device) with coordinates. So people 'at home' know where you are, that you're in some kind of trouble, and that it's probably not immediately life-threatening (because then you would have pressed the other button), but that's about it. Using a sat phone gives allows you a lot more options.

Note 2: If you look at the pictures above, you'll notice that there's an old-fashioned dial phone hanging on the wall. Why didn't we use that? After all, we're probably were all old enough to remember how dial phones worked... But the trouble was that this was just left in there for ambience. The hut used to be located somewhere nearer to Inuvik and at that time was connected to a regular phone line. It later got moved to Shingle Point (where there isn't a phone line - or much of anything else) and the phone was just left hanging on the wall. Nicely nostalgic to look at, but not useful in an emergency.

Calling emergency services on the sat phone gave us an answer that surprised us (or at least surprised me). They could get Chuck out and fly him to Inuvik in a couple of hours. Unless it was a medical emergency. In which case it would take about four days.

Which seems kind of strange for people living in a city where emergency response times are supposed to be less than 15 minutes. And not measured in days. And having a non-emergency response quicker than an emergency also was counter-intuitive.

However, it made sense in the situation we were in.

There are helicopters available for charter in Inuvik (mostly for moving crews to remote mining camps, but also for flightseeing and other recreational use). So if a normal helicopter can be used, it's just a case of getting it ready, flying over to wherever it's needed (assuming there is some place to land), taking a passenger on board and flying back.

But that assumes that whoever needs to be flown out can function as a normal passenger.

However, if someone needs medical attention during the flight, needs to be transported lying down or is unconscious, a helicopter specifically equipped for search and rescue is needed. (There's probably also a problem if you're stuck in a place where a helicopter can't land, such as being stuck on an ice floe drifting at sea and you need to winch someone up.)

And there's no such helicopter in Inuvik.

So if you need an emergency medical evacuation, the helicopter needs to be flown in from somewhere else (probably Edmonton, about 2000 km away), which takes some time. But to complicate the situation, a storm front was approaching. By the time a rescue helicopter would probably have gotten to Inuvik, it probably wouldn't have been able to get out to us and would have had to wait until the storm was over (most likely about three days).

The whole thing reminded me part of an old Phil Foglio cartoon. While the cartoon was mainly about the differences between science-fiction and fantasy, it had this to say about calling for help in emergency situations:

The upshot of this: In a place like the one we were in, it's probably best not to have a medical emergency. (But then, there are few places where you want to have a medical emergency, so it's not very useful advice.)

But as Chuck didn't feel any pain and didn't have any other problem than seriously frostbitten toes, so calling in a helicopter from Inuvik was sufficient.

In preparation, we started to look for a landing place without any big snow drifts for the helicopter to land on and put out some orange fuel cans to mark the landing site.

The sky was overcast that day, which made it hard to see any surface features, even when standing right next to them.

As an example, here's a view towards the other (mostly private) huts at Shingle Point.

And any ground feature would be much harder to see from above. Also, setting up the landing site for the helicopter gave us something to do.

Originally it was planned to stay at Shingle Point only for a night and continue the next day. But that was planned under the assumption that it would take us two days to get from Shallow Bay to Shingle Point and that there wouldn't be any emergencies. Since everyone was tired after the long run on the previous day and we needed to wait for the helicopter, the day became an additional rest day.

Obviously, the dogs enjoyed getting a bit of rest.

It was also a good opportunity to do some maintenance work on gear, including drying stuff and sorting through booties.

We probably had enough booties with us to put on new ones on the dogs every day (in most cases you don't want to re-use booties during a trip as it's hard to get them properly dried in a tent or next to a fire outside), but generally booties are re-used on subsequent trips. However, they have a limited durability and you don't want to use booties that are damaged. Sitting in a warm hut gave us the opportunity to get the booties used so far (and everything else) real dry, the chance to check every one of them of damage and the time to sort them again by size. The 90 kilometer tour on the previous day was pretty close to the limit for a lot of them, with the cloth either worn through or very thin. The orange booties were of much sturdier cloth and rarely looked worn out. (Most of the orange booties that needed to be thrown away were the ones where dogs had ripped off the velcro when trying to take them off.)

It also turned out that two of the dogs seem to have problem, so it was a good time to bring them in and check them. Gandalf was moving oddly and had some problems with his shoulder, while Kake had a swollen wrist.

It was fascinating to see how differently the dogs reacted to being brought into the hut.

Kake (image above) was obviously more concerned about being brought into the hut than having a swollen wrist. It was difficult to get him into the hut in the first place, with him trying to pull away from it. And in the hut he stood there very nervously, tail tucked between the legs and generally not being a happy dog. (And all that just because of being inside. It obviously didn't have much to do with the wrist, since Kake behaved fairly normal when being outside. Usually the dogs are very sturdy anyway. If you didn't notice the swelling, it was hard to tell from his behaviour that he was hurt at all.)

Gandalf, on the other hand, took to the hut as if he had spent there most of his life and just came back from having a short walk outside. He just walked in, had a short look around and then just hopped onto the bunk bed as if that was his usual place, tried to lie down while touching as many people as possible and wanted to get petted by all of them.

The difference in behaviour between the two dogs was quite striking.

In the meantime, the scheduled time for the helicopter to arrive had come. Chuck had is gear packed and we went outside to wave him good-bye.

Soon the helicopter arrived.

While I had expected this after a similar experience some years ago, I still found it interesting that the dogs didn't take much notice.

It's not as if they see a helicopter every day (probably they've never been close to one before). (Some of the elder dogs back at the camp, especially Mischief had flown in a helicopter years ago when they were evacuated during a troublesome Yukon Quest. But none of them were travelling with us now.) And helicopters aren't particularly inconspicuous or quiet. But most of the dogs just looked up for a moment, noticed that this was some human activity that didn't immediately concern them and went back to rest.

The helicopter had landed and turned of the engines and the pilot (Chris) had come out to bring Chuck and his luggage to the machine.

One final wave and they flew away, while we stood there and watched them leave.

And then there were just seven of us left.

Later update: They had already send a plane to Inuvik, so Chuck didn't go to the small hospital in Inuvik, but transferred at the airport and was flown down to Whitehorse. Seemingly they did good work there - he kept all his toes.

We spent another night at the hut. At least there was one thing we didn't really have to worry about when going to the outhouse.

It's not as if there aren't potentially any bears around. But the advantage of being dogsledding is that you have 27 sentinels outside. So if there's a bear around, that still means trouble, but at least you're not going to be surprised by one that you didn't know was there. The dogs most likely will let you know. (At least that's the assumption. On the other hand, probably none of the dogs had seen or smelled a polar bear, so there's always the chance that they pay them as much interest as they were paying the helicopter...)

While we didn't see any bears or signs of them (when we were in roughly the same area in 2009, we had crossed polar bear tracks), Gerry met someone working for 'Parks Canada' while we were waiting for my flight back to Whitehorse at the airport. And he mentioned that someone had shot a polar bear not too far north from Shingle Point about a week after we had been there. Though the conditions were a bit different then. When we were there, there was no sign of open water. After the storm, supposedly a lot of the ice north of Herschel Island had drifted off. A polar bear tends to hang around the open water line, the bear might have ventured closer to Shingle Point than at a time where the ice extended much farther.

Next morning the weather was still mostly the same as the day before. Overcast skies and a bit of wind, but not that much of it.

But due to the information from the previous day (and also because Chris, the helicopter pilot, had mentioned the upcoming bad weather briefly), Frank decided to use the sat phone to call in and get a current weather report. (Ours was about four days old by then. And while the weather forecast was marvellously accurate for three days or so, it quickly deteriorated into a random prediction beyond that. So we didn't really have any meaningful forecast for the days to come.)

The forecast wasn't too good. There were going to be some serious winds with speeds of 70-80 km/h coming up from the direction of Herschel Island and lasting for about three days.

Which meant that it made no sense to try to travel to Herschel Island. Our schedule allowed for six days of getting to Herschel Island and back to Shingle Point and it's a two day trip each way under normal conditions. So if we tried to get there and then got stuck in a storm for three days, then there'd be no way to get back to Shingle Point on schedule. And everything needed to go right if we wanted to make it back to Inuvik on time. Given the trip so far, we didn't really want to rely on nothing going wrong. Also, nobody wanted to head towards a storm and risk to get stuck in it for a couple of days anyway.

And nobody really needed to get to Herschel Island. It's was just a convenient destination for a dogsledding trip from Inuvik - the right distance and something to aim for - but it's not like a mountain peak or the Poles, where it's a huge thing whether you reached your destination or didn't.

So Frank and Gerry decided that it would be best not to try to get to Herschel Island, turn around and try to get away from the storm.